Helping people learn via examples is a basic tenet of most instructional design. Abstract concepts become concrete through example.

Building on the idea of learning through examples, if you provide multiple examples to people learning a new idea, it usually leads to a better understanding of how the abstracted concept was derived. Thus the abstracted concept, or theory is just a way of explaining why the world works as it does.

Perceiving what to perceive: contrasting cases

However, when an individual is new to a domain, how they know what to look for? How do the know what is important? What is relevant to notice? This is where the design idea of contrasting cases comes to bear. Learners are given an example, then asked to derive an explanation of a pattern or what they see in front of them. Then they are given another example — a contrasting case — which is significantly different from the prior case or example. The learner then has to explain both cases. They have to create a model that can encompass both examples.

What the learner is doing is perceiving salient differences through multiple contrasting cases. Or as Daniel Schwartz & John Bransford write an article in 1998 called A Time for Telling: “analyzing contrasting cases can help learners generate the differentiated knowledge structures that enable them to understand a text deeply.” By learning how to perceive salient differences through multiple contrasting cases, and by creating new schema or mental models from learners’ own experience, learners created their own base of knowledge from which to further understand a concept.

A time for telling

After deeply engaging with material through contrasting cases, the learners are then more prepared to receive a lecture on the subject. “Noticing the distinctions between contrasting cases creates a ‘time for telling’; learners are prepared to be told the significance of the distinctions they have discovered” (Schwartz & Bransford.)

Analogies: a special kind of case

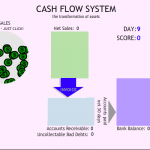

Likewise, having multiple, appropriate analogies or examples helps learners incrementally develop increasingly abstract schemas, especially if they are able to apply it to problem soon after learning. An analogy is a particular type of case that compares a concept familiar to a learner (the source) to an unfamiliar concept (a target). For example, comparing a plumbing system to the concept of cash flow, drawing a relationship between cash and the flow of water, between leaks and the loss of cash through bad accounts and interest. Based on this comparison, learners draw inferences about a target that deepens or elaborates their understanding.

Likewise, having multiple, appropriate analogies or examples helps learners incrementally develop increasingly abstract schemas, especially if they are able to apply it to problem soon after learning. An analogy is a particular type of case that compares a concept familiar to a learner (the source) to an unfamiliar concept (a target). For example, comparing a plumbing system to the concept of cash flow, drawing a relationship between cash and the flow of water, between leaks and the loss of cash through bad accounts and interest. Based on this comparison, learners draw inferences about a target that deepens or elaborates their understanding.

Analogies are powerful tools for helping learners understand a new domain. The challenge is choosing an analogy that maps not just surface elements but that also maps relationships between the elements. For example, in the cash flow/plumbing system analogy, a hot water tank could be analogous to accounts receivable, a place where sales/incoming water is held before being transformed into cash bank balance/or hot water for the house. Even in this example, the analogy is a bit strained as water does not fully capture the transformation of cash as an asset as it moves through the system.

Analogical reasoning also depends on some prior knowledge of the source. However, even if the source is not completely understood by the learner it can still be helpful in learning. It is the comparison of the two cases, the source and the target, and examining their similarities that facilitates the creation of abstract concepts and schema.

Great post. This idea of showing examples as part of the learning process is something I bring up in my most recent post, regarding a how some science teachers (being inspired themselves) get their students excited by actually demonstrating what some of the laws of physics can be.